workshops, conference demonstrations & interviews

“Armstrong gives a demonstration, a sound journey. Thousands of feelings and emotions surround us: love, innocence, hate, jealousy, humour, madness. His voice travels through all the ranges, textures and colours, from a tearing scream to the melancholy song of a trumpet, at moments managing to make two or even three sounds simultaneously. Extraordinary to hear a person making chords with the voice. But it’s not a circus act presenting the voice as a phenomenon: it’s a demonstration of vocal training, an investigation of the sound possibilities that everyone possesses, a fact which makes us appreciate the work even more.”

“Towards the end of the interview, Richard Armstrong suddenly voices in pre-lingual terms, everything he’s been talking about. He opens his mouth wide and releases, as if from his whole throat, a dense, visceral, actual chord – an octave, rich with overtones. Inhuman, if we didn’t know that the Tuvans and the throat singers of the Arctic can do it too.”

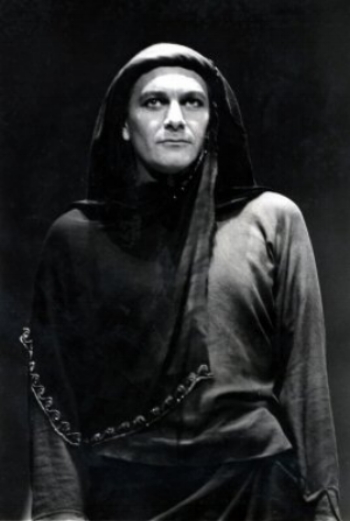

“His students follow him around the world, flying thousands of miles to take yet another workshop. In class he has the noble bearing, the sureness and beauty of a lion and yet presents the work simply and in a manner that never encourages his students to make a guru of him.”

“The sounds Armstrong unleashes with his vocal, movement and breathing exercises are valuable currency in contemporary music theatre. Never one to put bel canto on a pedestal, he is as fascinated with the vocalization that might accompany a tennis shot as he is with a perfectly positioned high C. He cultivates impure sound – the peeps, motor-like rumbles, multiphonics and whistle tones that are more typically associated with various ethnic musical traditions (Inuit throat singing, Tuvan overtone singing and the chanting of Tibetan monks) with the same diligence that others give to singing on pitch”

“For many of us, this was the first encounter with such work; I think I can speak for many, when I say we were left astounded by the vocal explorations of Richard Armstrong and his associate.”

“The work achieved by Richard Armstrong last night was impressive: beginning with sound like a whirlwind caught in a rare concentration, he moved to sounds which seemed to come from an obscure cavern in the centre of the earth. From this centre of the sould he guided us to places unknown, revealing a dragon’s mystic body incarnated in a mortal form, and the incredible perception and capacity rooted in the human being.

Suddenly we climb vertiginously, with incredibly high notes, to the sky, which in turn becomes the universe; we hear the desperate cry of a bird in search of its mate, the cry transforms itself into harmony, singing and melody; the wind blows, a stream flows; in a moment of silence fear and hopelessness are replaced by courage and faith. In the calm that follows we are between the sky and earth, silence and voice. And there are so many doors...”

performing and directing

Eight Songs for a Mad King music theatre by Peter Maxwell Davies, performed by Richard Armstrong with the Helikon Ensemble, conducted by Leslie Dala

“We know this: when it comes to music-theatre productions, an actor who can sing is far superior to a singer who can’t act.

.... Richard Armstrong took the lead, performed in the original 1969 production by his mentor, Roy Hart, and the singer’s intimate acquaintance with the work was immediately evident. (Armstrong, a gifted director and visual artist as well as a remarkable singer and actor, also designed and built the premiere’s set.) He seemed comfortable in his madness, insofar as anyone can be comfortable in a role that asks the performer to bellow, shriek, whisper, and twitter-and no matter how extreme his vocalizations, how nonsensical his rants, their meaning was always clear.”

“...At the Vancouver East Cultural Centre on Sunday, Peter Maxwell Davies’s Eight Songs for a Mad King, had the timelessness of King Lear...... The soloist makes or breaks these compositions, which revolve around an extended vocabulary of vocal sounds that range from bel canto to primal scream. Ricahrd Armstrong made his.

Richard Armstrong’s mad king George III was great theatre, pure and simple. Was it an opera? Was it a play? Was that speech or was it song? Who cares? That type of categorizing becomes irrelevant in a performance as vital and integral and as emotionally coherent as Armstrong’s: Every sound he uttered had dramatic potency; every sound he made was a kind of music...

It would have been easy for Armstrong to turn Eight Songs into a virtuosic display vehicle for his remarkable vocal skills. He truly does have a four-octave range and he uses it. He can split his voice into seperate threads of sound until it makes a scratchy chord or an eerie octave – in other words, he can sing along with himself. He can move from a whistling falsetto to a grumbling bass in a split second, cluck like a chicken, bellow like a blustery baritone from a Rossini comic opera, or whine like a fishwife. Bet we realize, listening to Armstrong, that great actors – and human beings in extreme emotional situations – make theses very sounds. They have a kind of terrible beauty, yes. And they are out there, all the time. In this, Armstrong is like a fine Shakespearean actor who, as a matter of course, ranges all over his vocal map to find the sound that expresses most powerfully the emotion his text presents to him.

By stringing these sounds together into a melody, and plotting them to an ensemble accompaniment, Davies invites us to hear this as music. But Armstrong, who is a superb physical actor as well as a vocalist, never lets us forget that the piece is, first and foremost, dramatic. “Pity me,” his character says at one point. And we do, for Armstrong’s mad king is real to us, pitiable, lovable, frightening, hopeless, comic and beautiful. We no more dissect the individual ways in which Armstrong conveys this to us – with his face, with his timing, with the shocking turnabouts in his voice – than we would watching a magnificent performance of Lear.”

Down Here on Earth opera by Rainer Wiens, libretto by Victoria Ward

“...when Krucker and Armstrong use their extraordinary voices to shed light on the nightmares bubbling just below the surface, this work has striking impact. Both can produce pure vocal sounds with excellent diction, but it’s their enormous range both in register and expression that startles the listener. They croak and cackle, shriek and moan, go real deep and real high, sometimes squeezing out notes like blackheads as they struggle to find reason to survive amid their desperate loneliness.”

“Wiens could have no more committed performers than Armstrong and Krucker, where eagerness to croak, shriek, scream and approach singing gutturally is always directed toward expressiveness. Armstrong, in particular, makes his wide range sound natural, animated by brilliant diction.”

“The singers-actors – for which we would be tempted to use the neologism sometimes attributed to Pauline Vaillancourt of “chantacteurs” - play their respective roles with intensity. Richard Armstrong in particular is deeply moving, and his performance so inspired that we can hardly imagine him outside the character of Red. The vocal work is another very successful aspect of this Autumn Leaf Performance production. Far from the grand flights of traditional lyric, the voices of the singers are intelligently used and for a specific aim. Down Here on Earth shows beings living on the edge of society, full of rage and pain. Their voices serve to express this rage and pain through sumptuous controlled cries, exploring deserted zones of the human voice.”

Furies an international collaboration by Roy Hart Theatre and Talking Band

“Coming out of the theatre, after seeing Furies, one is astounded. Furious jazz harmonies, pushed to extremes never yet thought of, are heard in the voices. Could one use the Roy Hart Theatre ‘method’ for any theme?”

“A gripping, stunning display of elemental horror. The cast presents the furious passion of the work with the directness of a bullet. Richard Armstrong’s Clytemnestra shimmers with tension; hhis deep resonant voice and chiseled face make a perfect connection.”

“The best work comes from Richard Armstrong of the Roy Hart company, who offers a Ludlumesque Clytemnestra, campy but poignant; he achieves the most interesting extensions of speech in the direction of song, and his lapses into French are somehow nicely eerie.”

“A performance of an extraordinary originality and grandeur... a wonderful baroque African opera of fantastic beauty.”

The Star Catalogues by Owen Underhill, directed by Richard Armstrong

Subtle Surprises Ahead works by Aperghis, Metcalf and Rzewski, directed by Richard Armstrong

Water and Gravity the music theatre of Georges Aperghis, directed by Richard Armstrong

“This astonishing work of music-theatre is so compelling, so masterfully allusive... that if the world of contemporary opera were ranked along a similar chain of being, The Star Catalogues would find itself somewhere near the top, in the company of works by Poulenc, Britten, and Janacek. Full credit for a rich staging to directors Richard Armstrong and Penelope Stella. A troupe of singers, actors, and dancers move fluidly through the set, sometimes acting as chorus, sometimes as stagehands... the most impressive new work from Vancouver artists in decades.”

“The staging was minimal, the music minimalistic. But it was no small affair: Surprises is a funny, touching and exhilarating, prepared with thoroughgoing seriousness yet never afraid to turn giddy in sheer delight with speech, song and the body as vehicles of uninhibited virtuosity, Richard Armstrong’s direction, here and elsewhere on the bill, was a perpetual high-wire act in which his actors were the assured acrobats.”

“Armstrong’s cast of 14 performers-Jean-Pierre Drouet’s musical direction- rise to the difficult task of learning Aperghis’ intricate notation by heart, and performing it without a conductor. The results are admirable. Luckily, most of the cast have previously participated in the unique kind of extended vocal and body training that Armstrong has been conducting for years at the Banff Centre, and the result of this shows. The evening has a vital ensemble feel that makes the production seem effortless. Come see and hear this North American premiere: it’s side-splitting music theatre that’s to die for.”

El Cimarrón by Hans Werner Henze Performed in Banff, Toronto, Atlanta, Madrid, Munich, and New York Vocal direction by Richard Armstrong

“Faced with the difficulty of conveying a sense of German ‘sprechstimme’ in English, his extraordinary vocal range encompassed everything from an anguished wail to the dry iterations of spirits while less onomatopoeic sections of text were sung with deep feeling and impeccable diction... it was his voice that provides the production with its artistic centre.”

“Gregory Rahming, who performed the role here, was strong and alert, but also touching and lovable. There was sweetness in his voice, and even when speaking he was making music.”

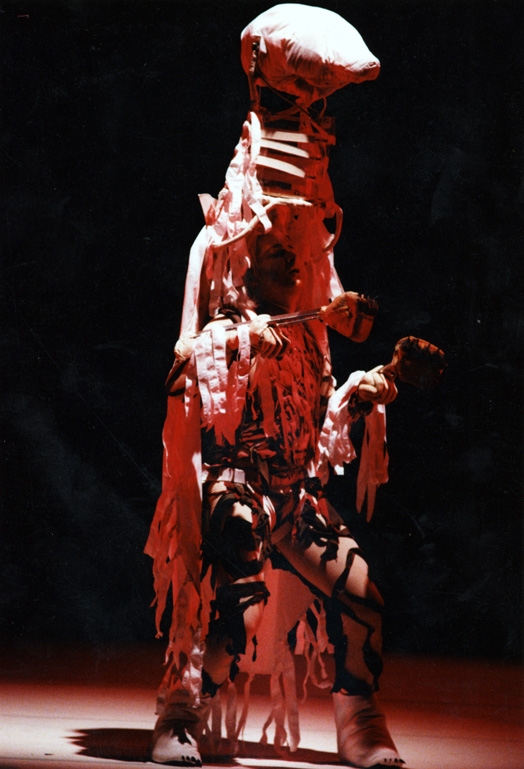

Tornrak an opera by John Metcalf, commissioned by Welsh National Opera, co-produced with the Banff Centre for the Arts. Preview in Canada in February 1990, World premiere performances in Great Britain in 1990. Broadcast by the BBC June 1990. Richard Armstrong worked with the composer for four years to incorporate extended vocal techniques into the score, and acted as extended voice coach for the production. The roles of the Polar Bear, a Polar Bear Tornrak, Utak, the voice of the Wolf Tornrak, and Frankie the bear were written especially for his voice by the composer.

“One of the extraordinary aspects of this opera is the wonderful aura created by the extraordinary performance of Richard Armstrong as the Polar Bear, the Wolf’s voice, Frankie the bear and various other haunting and marvelous sounds he produces with his extended voice techniques. We are drawn into this world of magic, seduced by both its visual and musical other-world, and the darkness is temporarily submerged to roll like the unseen mass of an iceberg in the ostinato of the orchestra.”

“First, that polar bear. It appears in John Metcalf’s Tornak, and later there is a fairground dancing bear. Both animals are the disguises of Richard Armstrong and are exceptionally successful, unlike most of their kind on stage.”

“Milak’s dialogue with the departing spirit of the Polar Bear is another emotional landmark. The throat-music exchanged between himself and Richard Armstrong creating an arresting tillness in the midst of the generally Messian-like activity at this point. Armstrong plays a major part in the success of this enterprise, bringing his expertise in extended voice techniques to the animals and spirits he portrays.”

“Richard Armstrong not only advised on special voice techniques but powerfullyplayed Milak’s dying father and took both bear roles.”

“One fascinating aspect of the performance was the successful integration into the musical texture of Inuit throat singing, done to great effect by Richard Armstrong in his roles as various bears and Tornraks.”

El Canto General music by Theodorakis text by Pablo Neruda

“Superb direction, truly inspired chorists, perfectly conducted. As for the soloists, how to describe their performance, notably that of Richard Armstrong? The heart-rending emotion, strength and sincerity of their singing.”

“It’s little to say that a voice such as that of Richard Armstrong is perfect for the force of such a work. One must remain humble, very humble before so much vigour, truth and power. Richard Armstrong experienced a total triumph, and what a ‘tour de force’ to have been able to repear the final piece with the same power after almost two hours of singing!”

Pagliacci by Leoncavallo, Roy Hart Theatre production, directed by Richard Armstrong

“Anyone who enjoyed Peter Brook’s Carmen and would like a rather bolder operatic rewrite should investigate the Roy Hart version of Pagliacci at La Mama.”

“The Roy Hart Theatre transforms Pagliacci into something difficult to define, which has to do with presence. It really works and is a little miracle of art.”

“Emotion. As if this evening on the stage of a theatre, something truly happened. Somthing, that could have a link with an origin, to a miracle.”

“This daring and virtuosic Pagliacci is a complete musical reworking and theatrical rethinking. While Leoncavallo refined his elements into bel canto, the Roy Hart Theatre uses the same elements to express raw, unrefined feelings – from secret, desperate love, to misery, to commedia fun, to rage and terror... multi-octave leaps from bass to clear, controlled falsetto... the voice quality is being precicely modulated for precise, sometimes stunning effects.”

Julie Sits Waiting a new opera composed by Louis Dufort, libretto by Tom Walmsley, starring Richard Armstrong and Fides Krucker at Theatre Passe Muraille, Toronto, 2012

“Krucker’s and Armstrong’s lofty, tortured-soul vocalizations – which regularly feature otherworldly left turns marked by sudden octave jumps, little shrieks, deep echoes and guttural sounds – mesh surprisingly well with Walmsley’s stark, street-level snapshot of two very real people faced with real-life problems.”

“...it gets, from Fides Krucker and Richard Armstrong, the virtuoso performances it demands, rigorously unglamorous but searingly passionate.”

“...a feast for the eyes and ears, worth experiencing for its stars’ vocal work alone. It’s also a terrific example of multimedia being used to enhance and drive opera forward, while never usurping its core.”

“...a show which cannot avoid inciting expectations given its team of internationally-acclaimed creators, performers, and designers. The Backspace at Theatre Passe Muraille is a most appropriate space for the juxtaposition presented by this powerful and dynamic yet intimate show.”

“Julie Sits Waiting is a small gem of complex proportions, bursting at the seams at every moment, giving the audience prolonged moments of spectacular sound and projection as the actors leave the stage, only to return to the fully engaged, and darkly invigorating story they tell through an incredibly diverse storehouse of physical and vocal brilliance.”

“Sometimes one encounters texts that don’t really need to be sung, or music that doesn’t connect to its story. But JSW is a synthesis of its media, requiring the words, the music, the singing & the theatrical presentation to work its magic.”